I’m concerned about the amount of “blockchain will cure cancer” type prophecies. Many of blockchain’s most vocal proponents are so ill qualified when it comes to understanding the technology yet they hum along singing the benefits. Don’t get me wrong. I’m a blockchain supporter, but I fear it’s being oversold and failures to live up to the hype will result in a backlash. I don’t claim to be the first to have these concerns.

This article is not meant to be an explanation of the technology of blockchains. If you’re interested in a technical discussion, there are many other resources. For our purposes, we can think of blockchains as a log. Now some people equate blockchains to databases, but I think the analogy is flawed. While both a database and a log contain data, a log implies a sequential series of entries, whereas a database implies the ability to read, write and edit in a non-sequential format. A blockchain is sequential. It has dates, times, and some data:

The log in a blockchain can be simple, as above, or complex, following a specific format for the data such as designating accounts to debit and credit and the associated amount. Many people refer to the blockchain in Bitcoin as a ledger, because it logs transactions, the debits and credits of Bitcoin owners. Blockchain log entries can encode bits of programmatic logic.1 But, whatever the format, in essence, a blockchain is a log full of entries.

Unlike a simple log file though, a blockchain has a bunch of fancy characteristics to enhance its security. First, blockchains use a cryptographic technique called hashing to preserve the integrity of the data. Second, blockchains use incentives to ensure that people maintain the log and add new entries to it. These people are called “miners”, with a historical wink to workers who mine precious metals. Because of miner’s need to earn their incentives, the log is widely shared, increasing its availability. Miners bundle up log entries in the queue into a “block” and then add those to the log. The blocks are “chained” to the previous block because each block includes a summary of the previous block.2 Hence, we refer to the log as a chain of blocks or a blockchain. The summary of each block must be of a certain format and it takes significant computing power to put the summary in that format.

Blockchains incent miners to build new blocks in two ways: they earn a “fee” for each entry they log and they earn a “reward” with each block they add to the chain. The fee is paid by people who want their transactions included in the block, which only shifts existing value from the transactor to the miner. The fee is like a percentage paid for someone to transport your gold from one party to another. Whereas, the reward actually increases the money supply. You can analogize this to a gold mine where finding a new gold vein increases the amount of gold in world.

But mining is a competitive enterprise, and only one miner can find a gold vein. In Bitcoin, only one miner can add the next block to the chain. Miners win the race for the next block by solving a very complex mathematics problem, which is why Bitcoin miners now use ASIC (application-specific integrated circuit) built to solve that problem. Having an army of miners creating new blocks further increases the integrity because an adversary would need to muster enough computing to match a majority of the miners. As of this writing, the Bitcoin network is calculating 10,470,748,203,000 megahashes per second and the computer you’re reading this on could probably calculate 50-60 megahashes per second.

Let’s return to our basics description. At its core, a blockchain is a log with a bunch of people competing for incentives (fees and rewards) to add to that log,

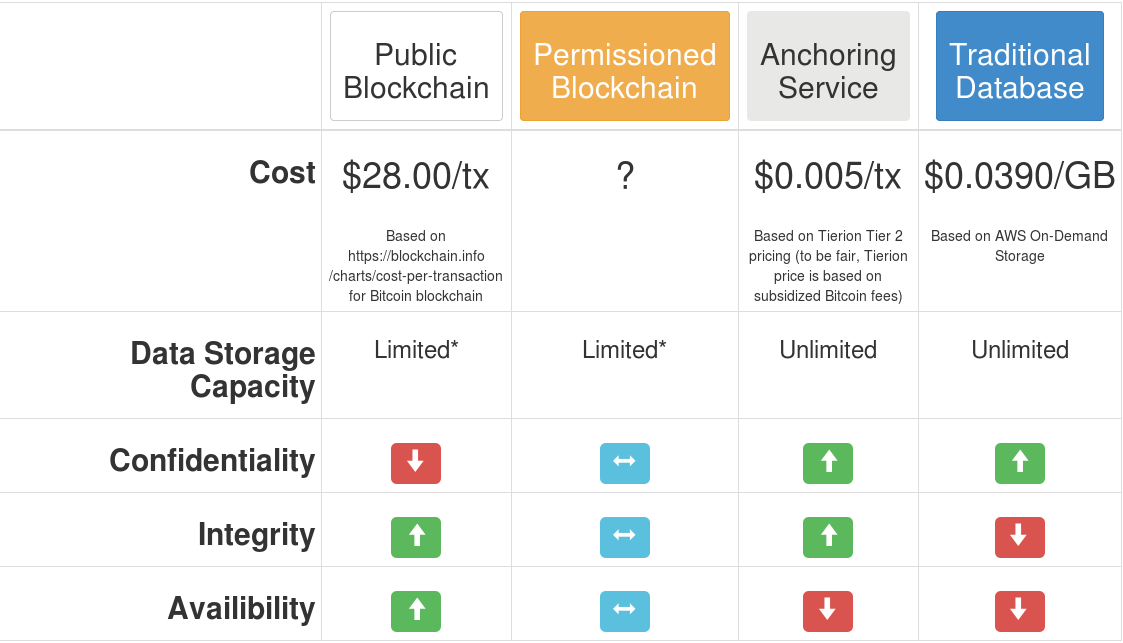

The cost of security

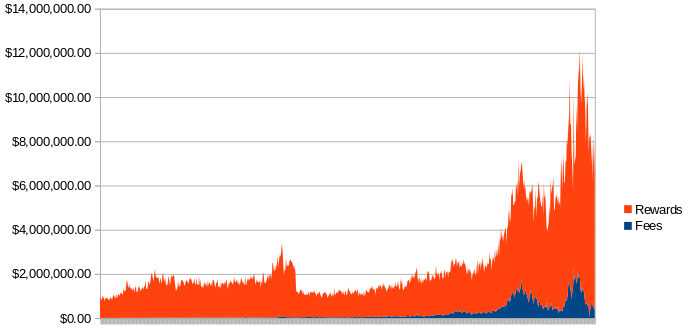

As mentioned above, the cost of running the network (storing the blockchain, running the computer that calculates the math problem, etc.) is approximately the same as the income generated by miners. The chart belows shows the daily income of miners for the last two years, based on rewards and transaction fees, currently running about $8 million dollars per day. If that amount is stable for a year, that would amount to $3 billion a year. The current market capitalization of Bitcoin is $62 billion. At this rate, we’re looking at about 5% to secure the network each year.

Illustration 1: Bitcoin daily miner earnings by transaction fee and rewards

Doing a back of the napkin calculation, Bank of America spends about $500 million dollars a year on security. Bank of America holds assets of about $2 trillion dollars. So the security budget is about ¼ of a tenth of 1%. Now to be fair, BofA relies on external parties to secure much of their assets; law enforcement and courts to bear the burden of catching and prosecuting thieves and fraudsters and the bank contractually shifts some of the risks to insurance companies, partners and others.

The point of this exercise was to illustrate that the cost of the blockchain can be many times more expensive than a methods of securing a traditional platform. This doesn’t mean that blockchain is not a viable option, but rather you have to weigh the value of what your securing against the costs of the solution.

For instance if you’re securing an international currency (like Bitcoin), having high integrity and availability might be worth it. If you’re securing something like the provenance of pharmaceuticals (subject to hundreds of billions of dollars a years in fraud) might be worth it. If you’re securing stocks, bonds, or real estates titles, then it might be worth it. But if you’re securing collectible cards on a blockchain, the value of the data isn’t worth the cost incurred. What’s throwing a wrench in the economic analysis of most blockchain start-ups is that (look at the chart again) the inflation of the currency is subsidizing the security costs. Blockchain users pay the transaction fees. But because demand is exceeding supply for the currency of blockchains, the price of the fees is small relative to the value of the rewards, obfuscating the true cost of the service provided by the miners.

One way to overcome this cost is the use of an anchoring service that doesn’t store data in the blockchain but aggregates a lot of data into one log entry (a digital proof of the data’s existence) to store in the blockchain. Consider a car title where I try to sell you a car with an altered title. With the digital proof stored in the blockchain, you could reject the title knowing it was altered. We reduce cost because we don’t have to store the actual document, only the digital proof. We increase confidentiality because the data is no longer stored in public. Of course, we lose something as well. We no longer have the availability of the underlying data; if corrupted, we can’t restore the underlying data; we can only prove it is, in fact, corrupted. This is great if you only need to prove data you have wasn’t altered, not so great if you’re concerned about restoring the original data if lost. Unless another copy of the real title existed somewhere, we’d never be able to reconstruct who actually had title.

Public blockchains.

Bitcoin uses a public (or open) blockchain. “Public” in this case means that miners are free to join and leave, and do so based on their own economic interest. If a one can make money in the business of mining, more miners will contribute to the network. If miners are expending more resources than they are earning they will exit the network. The creates somewhat of an equilibrium such that the money earned by the miners is very close to the costs they spend securing the network.3 Profit margins in blockchain mining are dependent on the miner’s underlying costs (mostly hardware and electricity) and the fluctuations in the value of the currency mined.

By contrast, permissioned blockchains are not public. An external structure governs participation, limiting who can act as miners. Thus, permissioned blockchains don’t exhibit the same economic properties as public ones.

What blockchains are good for

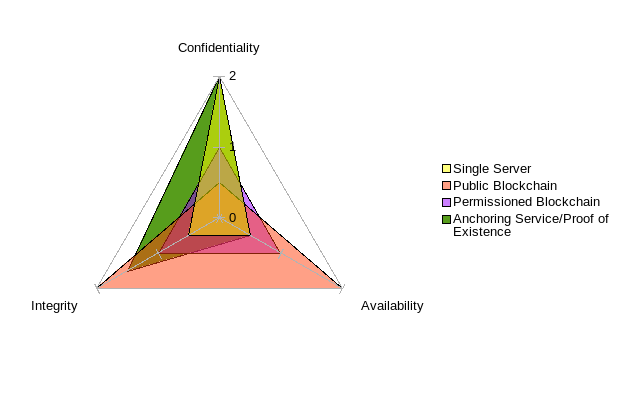

Now that we understand what blockchain is, we can start investigating appropriate uses of the technology. The simple fact is, wherever you have a need for a high level persistence (i.e. availability) and integrity, blockchain technology could be of benefit. I stress could, because you have to weigh two factors. The first is the true cost, as previous discussed (taking into account current subsidies). The second is a lack of confidentiality; the transaction data held on a public log. Of course, you could encrypt the data but it is still public and, because of its persistence, runs a higher risk of becoming completely transparent if an adversary compromises the encryption key. Unlike an encrypted private database which has the added protection of having limited exposure, a public blockchain is, by its nature, available to anyone, including an adversary. Even encrypting the data exposes meta-data, such as dates and times of entries, to analysis. As mentioned above, using an anchoring service, you can trade off confidentiality with integrity and availability, but you must determine an appropriate balance for your objective.4

Illustration 2: The trade-off among confidentiality, integrity and availability.

Interoperability, the snake-oil of the blockchain world

The most common fallacy in proposals to use blockchain is using it for interoperable data sharing among disparate parties. Participating parties in a blockchain network agree on a standard data structure, so in that respects they are, by design, interoperable. But one doesn’t need a blockchain for interoperability, one only needs an agreement on structure of the data. When I hear about proposals to use blockchains for patient health records (PHR), I cringe. Patient health records are in need on interoperability, so health care providers can share patient data with each other for more efficient health care. But blockchains lack enough confidentiality for patient health records and are an expensive means of providing interoperability. Anchoring services could maintain patient confidentiality but lack the interoperability that most providers in this industry seek. The underlying data, anchored to the blockchain, still needs an agreed upon data structure, which can occur with or without blockchains.

Smart Contracts

One of the more interesting structures of data to use in a blockchain comes in the form of programmatic code. Miners can execute that code as they build the block. Bitcoin has a simple scripting language (see https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Script), a sort of machine language for the virtual Bitcoin machine. Ethereum has a much richer programming language which allows such things as smart contracts to run on the network. What is a smart contract? Its an agreement between two (or more parties) that is self-executing. In a typical contract, when two parties agree to something, they must act on that agreement. If I agree to pay you $10 if it rains tomorrow, then I actually have to transfer that $10 if it does rain tomorrow. If I fail to do so, you have to enforce that contract through some means, suing me in court if you want to pursue legal means or beating me with a rubber hose if you want use extra-legal means. A smart contract executes itself. The parties put money in escrow with contract. The contract distributes the money to the parties according to the terms. This eliminates counter-party risk, the risk that the other party in a contract will fail to live up to the terms.

While such a program could run on a traditional server, if something happens to that server, the contract would fail to execute. This might create an incentive for the losing party in an agreement to tamper with or stop the server from running. Putting a smart contract on a blockchain network like Ethereum ensures it’s execution. Like confidence in the integrity of the accounting in the Bitcoin blockchain, Ethereum users are confident in the execution of the contract as written. But ensuring execution is not free and it’s not even cheap. It is a costly contract to execute. The blockchain holds the terms of the contract in perpetuity. It must run on thousands of computers. Users must compensate the miner for this activity. Now this might not be a problem, if the smart contract has significant value or counter-party risk. But no one would or should not use a blockchain for low value contracts with limited risk.5

Conclusion

My goal of this article was to pull away the veil of technological secrecy that sometimes comes with discussion of blockchain. For those without a technology background, it can be hard to distinguish between reality and snake-oil in the blockchain world. For those with a technical understanding, please forgive my over-simplification but it was necessary to help bring a wider understanding of the benefits of blockchain while separating out the more outrageous claims.

1The Bitcoin blockchain actually uses programmatic logic to build the accounting ledger. This what allows for sophisticated features such as multi-signature wallets. But that is out of scope of this article.

2That summary is in the form of a hash of the previous block.

3For more information about the economics of Bitcoin’s blockchain, check out https://helda.helsinki.fi/bof/bitstream/handle/123456789/14912/BoF_DP_1727.pdf

4Confidentiality, integrity and availability are consider the information security triad.